I’ve been teaching bioinformatics at the University of Delaware for roughly the last year now. I had never been in a bioinformatics class prior to teaching; my degrees are in ecology and marine science, so all of my bioinformatics knowledge came from research experience. It’s been really interesting to see bioinformatics taught in a formal setting. One thing I’ve noticed is the disconnect that can occur between students and instructors when students without programming experience are asked to perform “hands-on” exercises.

In an effort to de-mystify bioinformatics, instructors often have students manually perform a task that would normally be done computationally. While these exercises are valuable and often succeed in their goal, I have noticed that many students who are not used to being presented with code or equations tend to have difficulty implementing algorithms by hand, regardless of difficulty. This can cause students to shut down and question whether they are in the correct field, rather than empower them.

When this occurs, there seem to be two underlying issues: First, even at the collegiate level, many students are not confident in their ability to do math. This issue I will leave alone, as it cannot be solved in a single course or assignment at the graduate level. Second, the way that a computer would perform a procedure is not necessarily the same way a human would perform it. Sometimes, this can create a gap between students with little or no computing background and instructors who are highly familiar with algorithms.

In this post, I’ll walk you through the process of building neighbor-joining trees. Building phylogenetic trees by hand seems at first like a daunting task, but I promise it’s much easier than you think!

Neighbor-joining (NJ) is one of many methods used for creating phylogenetic (evolutionary) and phenetic (trait-based similarity) trees. The method was first introduced in a 1987 paper and is still in use today.

Neighbor-joining uses a distance matrix to construct a tree by determining which leaves are “neighbors” (i.e., children of the same internal parent node) via an iterative clustering process. A neighbor joining tree aims to show the minimum amount of evolution needed to explain differences among objects, which makes it a minimum evolution method.

There has been some debate about the mathematical behavior of neighbor-joining trees. Originally, neighbor joining was thought to be most closely related to tree methods that use ordinary least squares to estimate branch lengths, but further investigation showed that they actually shared more properties with “balanced” minimum evolution methods. You don’t need to know anything about these different methods in order to perform neighbor joining, but if you would like to read more about them, there is an excellent explanation in this paper.

The type of tree produced depends on the input. If you provide a distance matrix based on evolutionary data (e.g., multiple sequence alignment), you will get a phylogenetic tree. If you input distances based on non-evolutionary data (e.g., phenotypic traits), then you will get a phenetic tree. Note that a NJ tree doesn’t have to contain only organisms. You can make NJ trees for anything you can represent/compare with a distance matrix.

NJ trees are simple to make and require only basic operations (addition, subtraction, division), but can seem daunting because of the number of steps required. Here, I will show you how to make two small neighbor-joining trees by hand (or, by spreadsheet).

There are a lot of different ways to build phylogenetic and other trees, so how does neighbor-joining compare?

To begin neighbor-joining, you need a distance matrix. A distance matrix is a square matrix containing pairwise distances between members of some group. It must be symmetric (e.g., the distance from A to B is the same as the distance from B to A) and the distance from an object to itself must be 0. The distance does not necessarily need to be metric, but in at least one instance a metric distance slightly outperformed a non-metric distance.

Once you have a matrix, you can begin neighbor-joining.

The neighbor-joining process consists of three steps:

A quick note on the formulas (which can be found in the section below this one): You may notice a slight difference in the equations between this tutorial and another. Do not panic. These are only slight algebraic differences that do not affect the final answer, only the intermediate numbers.

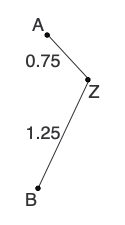

In the initiation step, we define a set of leaf nodes, T , and set L equal to the number of leaf nodes. These are the nodes at the “ends” of trees and therefore do not have any child nodes. You should have one leaf node for each item you want to compare. For example, if you are placing sequences on a tree, you will have one leaf node per sequence.

The iteration step is where most of the action takes place. Virtually all of our calculations are made in this step, and, as the name implies, we will repeat these calculations over and over until some conclusion is reached.

First, we calculate the net divergence (r) of each leaf node. You can think of this as being essentially the distance from each leaf node to all of the others.

Next, we calculate the adjusted distance (D) between each pair of nodes, which is based on the pairwise distance in the starting matrix and the divergence of each node. The pair of nodes with the lowest adjusted distance are neighbors and share a parent node.

Next, we declare the parent node and calculate the distance from each of the neighbors to the shared parent. This is also the step where I like to add the siblings and parent to the tree.

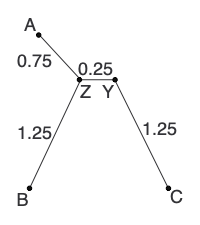

At this point, our goal is to construct a new distance matrix. To do this, we remove the two nodes that we earlier determined to be neighbors from the distance matrix and replace them with the newly formed parent node. New pairwise distances (d) are calculated between the new parent node and other nodes in the matrix. Any other distances (i.e., pairwise comparisons present in the new matrix and the previous matrix) can simply be transferred to the new matrix.

Note: In the formulas and calculations below, adjusted distances use a capital D , whereas pairwise distance use a lowercase d . Try not to get them mixed up!

One thing to be aware of is that, after the first iteration, the neighbors are not restricted to being leaves, and may in fact be internal parent nodes.

Each iteration step ends with a new distance matrix that is one node smaller than the one in the previous step (e.g., (L-1) by (L-1) after the first iteration). Iteration continues until there are only two nodes remaining in the matrix.

The final step is termination.

The only task remaining is to join the two nodes that remain after iteration with a single edge to complete the tree!

Now that we’ve braved the written explanation, it’s time to look at some examples to make all of these steps clearer!

These are the formulas for each of the calculations we will perform (you can find more formatted version in the excel file containing the examples).

Net divergence r for a node i with 3 other nodes (j, k, and l) :

Lastly, we need to reconstruct the distance matrix, replacing A and B with Z . Some distances can be transferred, but others (represented by question marks), need to be calculated:

| Z | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z | 0 | ? | ? |

| C | ? | 0 | 9 |

| D | ? | 9 | 0 |

Here are the formulas for calculating d(ZC) and d(ZD) .

Calculate any other new distances and construct the new distance matrix:

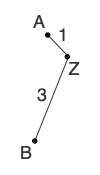

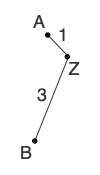

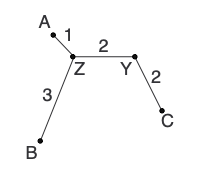

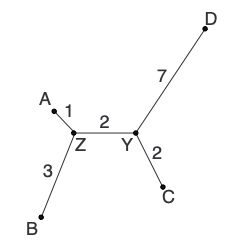

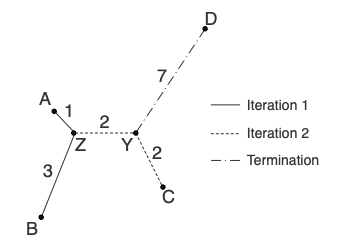

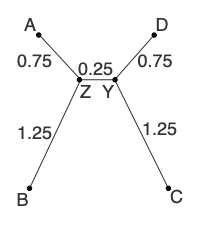

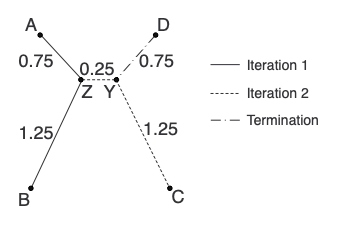

And with that, we’ve built our first neighbor-joining tree! Here is the tree coming together in each step:

Now, you may have noticed that to build the tree in Example 1, we didn’t actually need all of those formulas. In iteration 1, for example, we can figure out the distance from A and B to their parent just by noticing that B is always 2 units further from other nodes than A . Therefore, d(BZ) must equal d(AZ) + 2 . If their combined distance from Z is 4, then the only possible branch lengths are 1 and 3.

So, why did we go through the trouble of neighbor-joining? And when do we actually need neighbor-joining?

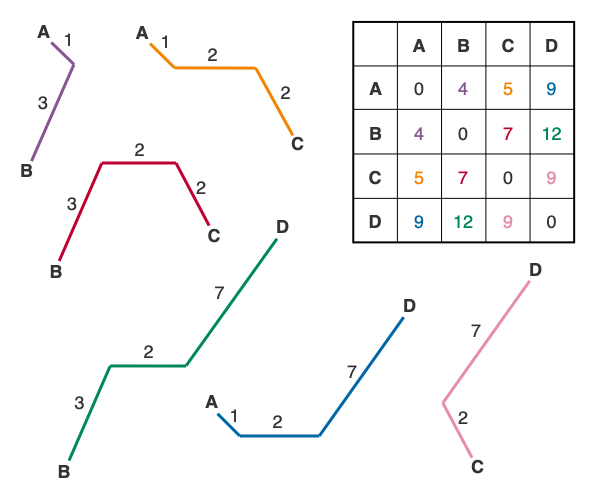

The distance matrix that we used for example 1 is what’s called an additive matrix. Simply put, a matrix is additive if you are able to reproduce the starting matrix by adding together the branch lengths along the paths between nodes. To demonstrate this, let’s look back at example 1.

In the figure above, I’ve deconstructed the tree so that you can see the individual paths between each pair of leaf nodes. Notice that we can reconstruct the starting matrix exactly using only the distances on the tree, which is the main trait of an additive matrix (for a more technical and thorough look at additive matrices, see this presentation).

I like to use an additive matrix as the first neighbor-joining example because, 1) it gives me an excuse to discuss additive matrices, and 2) it’s very easy to check your work. If you are unable to reconstruct the starting matrix in example 1 using the tree, you know you have a problem in your calculations, which is harder to catch with non-additive matrices.

Alright, so if we don’t need neighbor-joining for additive distance matrices, then when do we need it? Neighbor-joining is said to work best for near-additive matrices, i.e. matrices for which the tree almost reconstructs the starting matrix, though they have been reported to be topologically accurate even when this is not the case. And I should note here that the vast majority of distance matrices based on biological data are not additive or even nearly additive.

Without further ado, here is another example using a nearly-additive matrix.

Here is our starting matrix:

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| B | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| C | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| D | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Again, we define T and L . They are the same as example 1.

Lastly, we calculate new distances and reconstruct the distance matrix:

Calculate any other new distances and construct the new distance matrix:

Here is our second tree in completion:

Lastly, let’s make a distance matrix using the tree to provide the distances. Notice that these distances are just a little bit off from the starting matrix. Hence, “near-additive”.

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 2 | 2.25 | 1.75 |

| B | 2 | 0 | 2.75 | 2.25 |

| C | 2.25 | 2.75 | 0 | 2 |

| D | 1.75 | 2.25 | 2 | 0 |

Having reached the end of this lesson, you should have learned how to construct neighbor-joining trees by hand from additive and nearly additive matrices. If you want to take a closer look at the examples (and access one additional example), you can check out this excel file.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it on Twitter and subscribing to the RSS feed! If you have questions or comments, you can find me on Twitter or send me an email directly.